Artwork

Biography

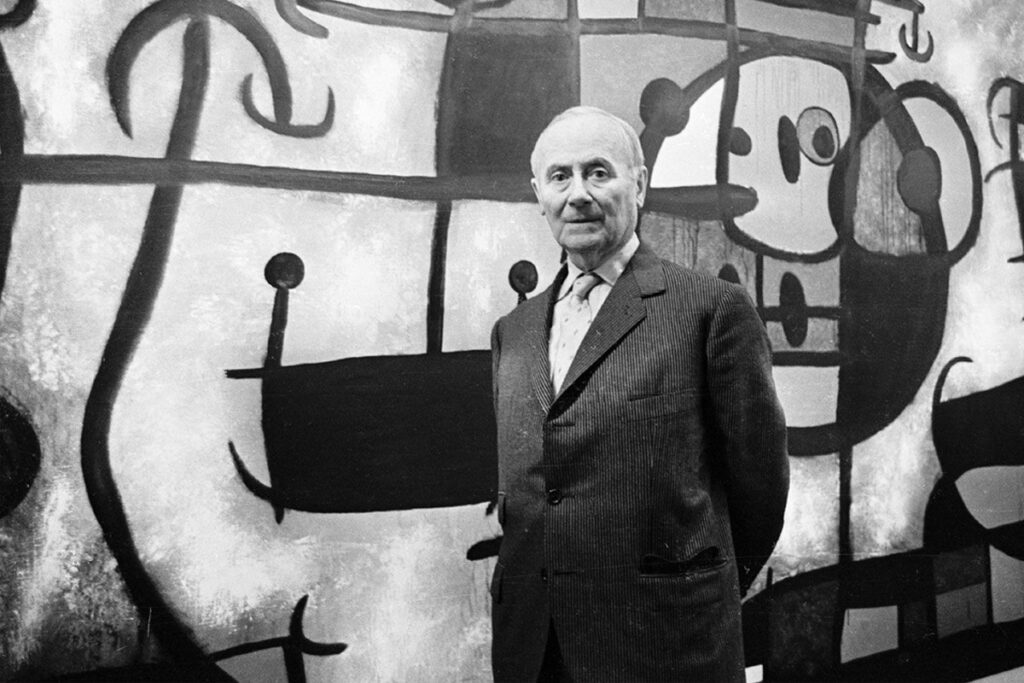

Joan Miró (1893-1983) was born in Barcelona, Spain. His father, Miquel Miró Adzerias, was a goldsmith and watchmaker. Being born into an artisan family surely gave an ideal artistic environment to nurture his creativity from very early in life.

At the age of just seven, he started drawing classes at a medieval mansion, Carrer del Regomir 13. In 1907, he went on to enter the fine art academy at La Llotja.

Miró had his first solo show at Dalmau Gallery in 1918, but it was not well received. His work was subject to mockery, and some of the pieces shown were even damaged and defaced. Alongside his experimentations as an artist, Miro undertook some drastically different studies at a business school. However, after suffering a nervous breakdown while working as a teenage clerk he discarded any notion of a career in business, and instead decided to direct all of his energies to work as an artist.

Like many of his artistic contemporaries of the time, Miró was inspired by the creative outpourings which were emanating from Paris. In 1920, he moved to Montparnasse to immerse himself in the artistic community, which was drawing revolutionary artists from all over Europe. Pieces produced this early period are often catagorised at Miró’s Catalan Fauvist period. This is due to the clear influence of artist such as Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne, who had also shown influence on other Fauvist and Cubist artist at the time.

Paris proved profitable for the artist’s development, and it was here that he managed to perfect some pieces which he had been working on during his stays at Mont-roig del camp – his family summer home and farm. ‘The Farm’ (a title showing a clear connection to the Catalonian influence) is often described as bearing the distinctive marks of Miró’s individualistic development. It encapsulates the way that Miro was able to absorb the typical, distinctive Spanish cultural styles into his own individuated working. The artist was praised for his ability to preserve identifiable traces of aesthetic history – traditional, nationalistic techniques and imagery which lay at the heart of his culture, yet rework them to capture in modernity the essence of what one feels in the experience of Spain. This Piece, bought by Ernest Hemmingway, was compared by the writer to being as successful a work as that of Ulysses by James Joyce. He reflected, “It has in it all that you feel about Spain when you are there and all that you feel when you are away and cannot go there. No one else has been able to paint these two very opposing things.”

Miró’s style became very distinctive. He perceived, imagined and created in a very different, nuanced way from his contemporaries and those before him, which immediately allowed his pieces to be identified and sets his works apart. Abstract like no other, Miró managed to synthesise vastly different influences in way that was executed with acute artistic skill and precision. The artist took inspiration from experiences as distant from the typical modern aesthetic as his early brushes with folk art and Romanesque church frescoes. Yet, he found ways to weave them in conceptual, metaphorical ways with ideas that germinated from interactions Surrealist like André Breton and others within this circle. From this he was able to achieve highly organised, culturally rooted, yet thoroughly modern compositions.

Though the philosophy and imagery of Surrealism had a strong influence on Miró’, he is generally considered to not belong to one particular school, and he certainly didn’t consider himself confined by any one set of principles or philosophy in the pieces that he created. The one defining concept that is consistent throughout the artist’s career is his concern with exploration of non-objectivity. Miró’s compositions of bronze installations, engravings, ceramics and print- making, all reflect his pre-occupation with biomorphic forms, geometric shapes, and a depiction of reality through the lens of semi-abstraction. In a similar vein to Picasso’s quest to ‘break apart’ reality, Miró strove to combine forms found in perceived reality with those that emanated purely from the artist’s mind. This gives his work enough basis in the tangible world to harness his abstractions, and prove identifiable for those who interact with them. In Miró pieces a simple subject, such as a dog, or a ladder, provide recognition, yet the morphed abstraction is made new, and intensified by his use of a limited, but exact palate.

One of Miró’s greatest legacies and importance in his place of the history of art stems from his use of colour. Working chromatically in a way that strove to emphasis the power of one unblended colour on another, Miró cemented a practice of colour use that was to inspire Colour Field painters of the next generation.